Researchers Save Information on a Single Molecule

Researchers at the University of Kiel (Germany) have succeeded in placing spin crossover molecules on a surface and improve their storage capacity, a development that would theoretically increase the storage density of conventional hard disks a hundred times.

Similar to normal hard drives, the so-called spin-crossover molecules can save information via their magnetic state. To do so, they have to be placed on surfaces, which is challenging without damaging their ability to save the information.

A research team from Kiel University has now not only managed to successfully place a new class of spin-crossover molecules onto a surface, but they have also used interactions which were previously regarded as obstructive to improve the molecule's storage capacity. The storage density of conventional hard drives could therefore theoretically be increased by more than one hundred fold, and data carriers could be made significantly smaller.

"The technology that is currently being used to store data on hard drives now reaches the fundamental limits of quantum mechanics due to the size of the Bit. It cannot get any smaller, from today's perspective," says Torben Jasper-Tonnies, doctoral researcher in Professor Richard Berndt's working group at Kiel University's Institute of Experimental and Applied Physics. He and his colleagues used a single molecule, which could be employed to encode a Bit, to demonstrate a principle which might just enable even smaller hard drives with more storage in the future. "Our molecule is just one square nanometre in size. Even with this alone, a bit could be encoded in an area hundred times smaller than what is nowadays required," says his colleague, Dr Manuel Gruber. This would be another step towards shifting the limits of quantum physics in storage technology.

The molecule which the research team uses can not only assume two different magnetic states, but when attached to a special surface, it can also change its connection to the surface. It can then be switched between a high and low magnetic state, and turned by 45 degrees. "When transferred onto storage technology, we would be able to depict information on three states - those being 0, 1 and 2," explained Jasper-Tonnies. "As a storage unit, we wouldn't have a Bit, we would have a Trit. Binary code would become trinary code."

The challenge for the researchers was in finding a suitable molecule and a suitable surface, as well as using the correct method to connect the two together in a way that would still allow them to work. "Magnetic molecules, so-called spin-crossover molecules, are very sensitive and easily damaged. We needed to find a way to firmly attach the molecule to the surface without affecting its switching ability," explained Gruber.

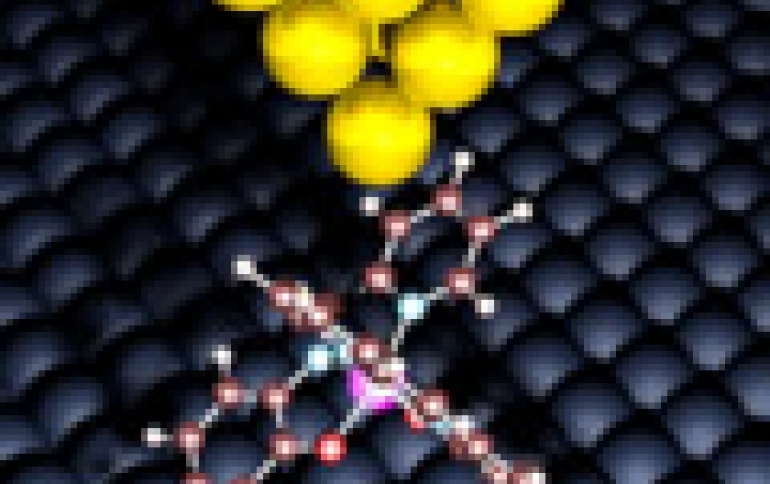

Chemists from Professor Felix Tuczek's working group at the Institute of Inorganic Chemistry synthesized a magnetic molecule of a special class (a so-called Fe(III) spin crossover molecule). Physicists Jasper-Tonnies, Gruber and Sujoy Karan were able to deposit this molecule on a copper nitride surface by means of evaporation. Using electricity, it can be switched between different spin states, and also between two different directions (in the so-called low-spin state). The fine tip of a scanning tunnelling microscope (STM) acts as a hard drive's reading and writing head in their experiments. This piece of equipment allows the molecule to not only be "written" as a storage medium, but also to be "read" using electricity.

The proof of principle is demonstrated using a rather voluminous setup (STM) but further work is required to integrate such a molecular memory on a small chip.