Microsoft Works On A Laptop Battery System That Adapts To Your Habits To Last Longer

Improvements in batteries haven’t kept pace with big advances in other aspects of computers and devices, such as faster processers and better screens. So researchers at Microsoft worked on a new approach to extending gadget battery life. Bodhi Priyantha, Ranveer Chandra and Anirudh Badam are among the researchers who have come up with a system that uses multiple kinds of existing batteries, working in tandem with smarter software, to keep laptops and tablets charged much longer than current standards.

"Rather than waiting for the perfect battery, we’re using all the technology available right now," said Ranveer Chandra, a principal researcher at Microsoft Research who is somewhat obsessed with extending battery life.

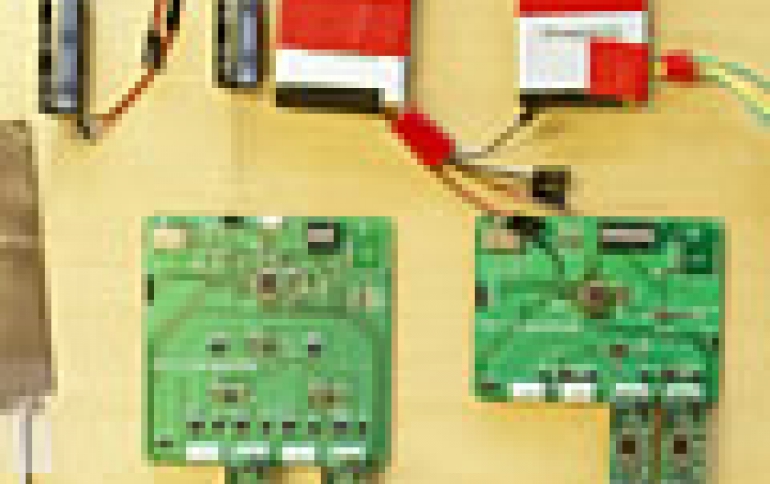

The researchers will present the project, called Software Defined Batteries, at the ACM Symposium on Operating Systems Principles next week. It’s still a research project for now, but they have built working prototypes and are hoping it will eventually be used in consumer products.

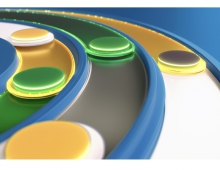

A typical tablet or laptop computer may contain more than one of the same kind of battery, all designed to charge and power the gadget in the same way. The system for managing that charge is generally handled within the hardware itself, rather than the operating system.

People are using their devices for more and more sophisticated things. That means they need different kinds of options, like a fast charge right before a big meeting or a more heavy-duty charge that can keep a computer powered through an international flight.

Microsoft's software-defined battery system takes a different approach. It combines several different kinds of batteries, all of which are optimized for different tasks, into the same computer. Then, it works with the operating system to figure out whether the user is, say, looking at Word documents or editing video footage, and applies the most efficient battery for that task.

The system also uses a technique called machine learning to learn from a user’s individual habits, so it can figure out how to extend battery life based on how that person is using the device.

For example, the system may recognize that the user plugs in the tablet every day around 2:45 p.m., and then gives a long PowerPoint presentation every day at 3 p.m. That means the computer needs to be ready to do quick charge at that time, so the person can make it through that afternoon meeting.

Another user may use the computer primarily for e-mail and Word documents during the day, then switch to surfing the web and watching videos on a train or bus commute home. Based on those habits, the computer can optimize the charge to make sure the user can do both without having to search desperately for an outlet.

As the research progresses, Chandra said he sees uses far beyond just laptops and tablets. This kind of thinking could eventually be applied to phones, cars and anything else that uses a battery, he said.