New 3D Chip Combines Computing and Data Storage

Researchers at Stanford University and MIT have built a new chip that uses carbon nanotubes and resistive random-access memory (RRAM) cells, providing several benefits for future computing systems.

Computers today comprise different chips cobbled together. There is a chip for computing and a separate chip for data storage, and the connections between the two are limited. As applications analyze increasingly massive volumes of data, the limited rate at which data can be moved between different chips is creating a critical communication "bottleneck." And with limited real estate on the chip, there is not enough room to place them side-by-side, even as they have been miniaturized.

To make matters worse, the underlying devices, transistors made from silicon, are no longer improving at the historic rate that they have for decades.

The new prototype chip is a radical change from today's chips. It uses multiple nanotechnologies, together with a new computer architecture, to reverse both of these trends.

Instead of relying on silicon-based devices, the chip uses carbon nanotubes, which are sheets of 2-D graphene formed into nanocylinders, and resistive random-access memory (RRAM) cells, a type of nonvolatile memory that operates by changing the resistance of a solid dielectric material. The researchers integrated over 1 million RRAM cells and 2 million carbon nanotube field-effect transistors, making the most complex nanoelectronic system ever made with emerging nanotechnologies.

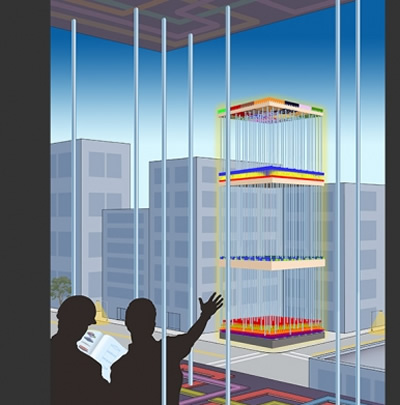

The RRAM and carbon nanotubes are built vertically over one another, making a new, dense 3-D computer architecture with interleaving layers of logic and memory. By inserting ultradense wires between these layers, this 3-D architecture promises to address the communication bottleneck.

Max Shulaker, an assistant professor of electrical engineering and computer science at MIT, says that such an architecture is not possible with existing silicon-based technology. "Circuits today are 2-D, since building conventional silicon transistors involves extremely high temperatures of over 1,000 degrees Celsius," says Shulaker. "If you then build a second layer of silicon circuits on top, that high temperature will damage the bottom layer of circuits."

The key in this work is that carbon nanotube circuits and RRAM memory can be fabricated at much lower temperatures, below 200 C. "This means they can be built up in layers without harming the circuits beneath," Shulaker says.

This provides benefits for future computing systems. "The devices are better: Logic made from carbon nanotubes can be an order of magnitude more energy-efficient compared to today's logic made from silicon, and similarly, RRAM can be denser, faster, and more energy-efficient compared to DRAM.

In addition to improved devices, 3-D integration can address another key consideration in systems: the interconnects within and between chips.

To demonstrate the potential of the technology, the researchers took advantage of the ability of carbon nanotubes to also act as sensors. On the top layer of the chip they placed over 1 million carbon nanotube-based sensors, which they used to detect and classify ambient gases.

Due to the layering of sensing, data storage, and computing, the chip was able to measure each of the sensors in parallel, and then write directly into its memory, generating huge bandwidth, Shulaker says.

Three-dimensional integration is the most promising approach to continue the technology scaling path set forth by Moore's laws, allowing an increasing number of devices to be integrated per unit volume, according to Jan Rabaey, a professor of electrical engineering and computer science at the University of California at Berkeley, who was not involved in the research.

One big advantage of the demonstration is that it is compatible with today's silicon infrastructure, both in terms of fabrication and design.

The team is working to improve the underlying nanotechnologies, while exploring the new 3-D computer architecture. For Shulaker, the next step is working with Massachusetts-based semiconductor company Analog Devices to develop new versions of the system that take advantage of its ability to carry out sensing and data processing on the same chip.

So, for example, the devices could be used to detect signs of disease by sensing particular compounds in a patient's breath, says Shulaker.