New Ultrathin Semiconductor Materials Could Replace Silicon in Future Electronics

The next generation of feature-filled and energy-efficient electronics will require computer chips just a few atoms thick. For all its positive attributes, trusty silicon can't take us to these ultrathin extremes.

Chip makers appreciate silicon's virtues include the fact that it "rusts" in a way that insulates its tiny circuitry. Two new ultrathin materials share that trait and outdo silicon in other ways that make them promising materials for electronics of the future.

Now, electrical engineers at Stanford have identified two semiconductors - hafnium diselenide and zirconium diselenide - that share or even exceed some of silicon's desirable traits, starting with the fact that all three materials can "rust."

"It's a bit like rust, but a very desirable rust," said Eric Pop, an associate professor of electrical engineering, who co-authored with post-doctoral scholar Michal Mleczko a paper that appears in the journal Science Advances.

The new materials can also be shrunk to functional circuits just three atoms thick and they require less energy than silicon circuits. Although still experimental, the researchers said the materials could be a step toward the kinds of thinner, more energy-efficient chips demanded by devices of the future.

As the Stanford researchers started shrinking the diselenides to atomic thinness, they realized that these ultrathin semiconductors share another of silicon's secret advantages: the energy needed to switch transistors on - a critical step in computing, called the band gap - is in a just-right range. Too low and the circuits leak and become unreliable. Too high and the chip takes too much energy to operate and becomes inefficient. Both materials were in the same optimal range as silicon.

All this and the diselenides can also be fashioned into circuits just three atoms thick, or about two-thirds of a nanometer, something silicon cannot do.

"Engineers have been unable to make silicon transistors thinner than about five nanometers, before the material properties begin to change in undesirable ways," the researchers said.

The combination of thinner circuits and desirable high-K insulation means that these ultrathin semiconductors could be made into transistors 10 times smaller than anything possible with silicon today.

There is much work ahead. First, the researchers must refine the electrical contacts between transistors on their ultrathin diselenide circuits.

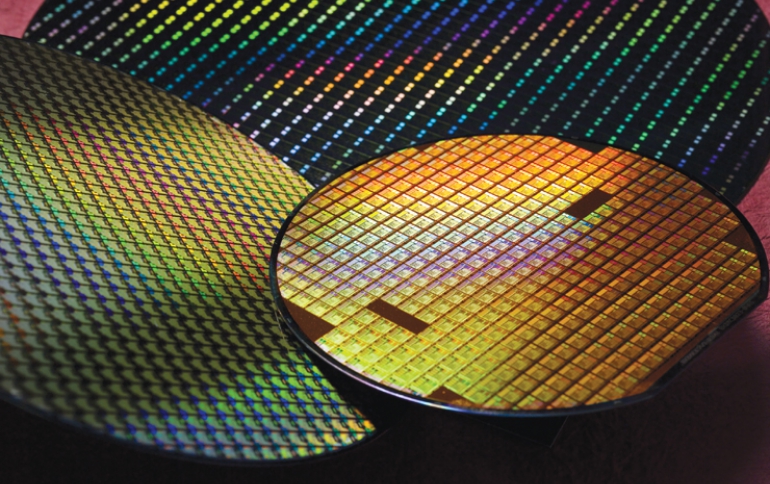

They are also working to better control the oxidized insulators to ensure they remain as thin and stable as possible. Last, but not least, only when these things are in order will they begin to integrate with other materials and then to scale up to working wafers, complex circuits and, eventually, complete systems.