3-D IC Engineering

Memory chip maker Matrix has developed a new generation of its technology, pushing forward in the quest for chips that are smaller and denser, and thus less expensive for use in consumer electronics.

Matrix Semiconductor of Santa Clara, Calif., is expected to announce on Tuesday that its approach - storing data in an array of circuits stacked in four levels - had yielded one-gigabit chips that are 10 percent smaller than its previous version and have twice the memory of the original 512-megabit chips.

The technology, called Trinity, offers a significant advantage against one-gigabit flash memory chips from makers like Intel, AMD and Infineon, which have on average three times as much surface area.

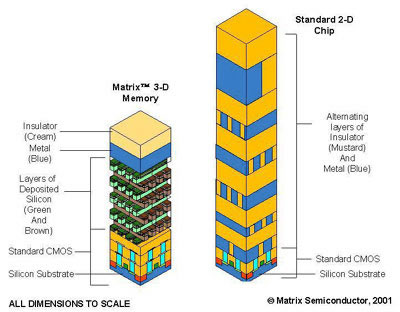

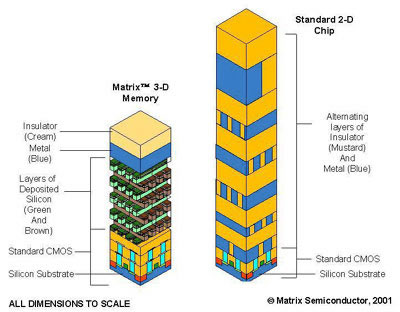

In conventional ICs, all active circuitry rests on the silicon substrate, with additional layers of insulators and interconnects used only for wiring and mechanical strength. In contrast, Matrix's unique 3-D architecture deposits multiple layers of active memory elements on a standard silicon substrate (or silicon surface) so that active circuitry is no longer confined to the silicon base, but extends vertically as well.

Matrix was founded in 1998 to exploit the third dimension in chip design. It announced last November that it had begun volume manufacturing of an initial generation of its technology - also in four layers, like a layer cake, with each layer storing millions of 1's and 0's. It currently ships more than one million chips a month.

While all computer chips are now composed of many layers of materials, Matrix has been the most aggressive in effectively creating semiconductor chips that have distinct levels, like separate floors in a building. The company's investors include Nintendo, Microsoft, Seagate, Sony and Thomson.

Power, size and cost constraints for consumer electronics products are all combining to lead to denser packaging technologies, including vertical chips. A number of chip makers are now stacking separate chips in packages to gain greater density.

Still, the niche does have its limits. The chips made by Matrix are programmable only once, as opposed to so-called Flash nonvolatile chips, which are used extensively in products like cellphones and digital cameras and can usually be reprogrammed several thousand times.

Matrix's immediate target for use of its chips is for mask ROM - chips that are loaded in the factory with data or programs that remain unchanged.

Matrix is also trying to exploit a manufacturing advantage over other memory chip makers: its ability to use older, less expensive chip making equipment. It can do so because the vertical approach means the circuits do not have to be etched as tightly to achieve the same capacity.

By using older technology, the company enjoys higher production yields, further reducing the cost of its products.

To build multiple layers - or floors - to pack its data more tightly, Matrix uses a layer of a material referred to as polysilicon to isolate each layer. This technology was first developed for flat-panel displays, where thin film transistors are placed on a thin layer of polysilicon which is then placed on a layer of glass.

The technology, called Trinity, offers a significant advantage against one-gigabit flash memory chips from makers like Intel, AMD and Infineon, which have on average three times as much surface area.

In conventional ICs, all active circuitry rests on the silicon substrate, with additional layers of insulators and interconnects used only for wiring and mechanical strength. In contrast, Matrix's unique 3-D architecture deposits multiple layers of active memory elements on a standard silicon substrate (or silicon surface) so that active circuitry is no longer confined to the silicon base, but extends vertically as well.

Matrix was founded in 1998 to exploit the third dimension in chip design. It announced last November that it had begun volume manufacturing of an initial generation of its technology - also in four layers, like a layer cake, with each layer storing millions of 1's and 0's. It currently ships more than one million chips a month.

While all computer chips are now composed of many layers of materials, Matrix has been the most aggressive in effectively creating semiconductor chips that have distinct levels, like separate floors in a building. The company's investors include Nintendo, Microsoft, Seagate, Sony and Thomson.

Power, size and cost constraints for consumer electronics products are all combining to lead to denser packaging technologies, including vertical chips. A number of chip makers are now stacking separate chips in packages to gain greater density.

Still, the niche does have its limits. The chips made by Matrix are programmable only once, as opposed to so-called Flash nonvolatile chips, which are used extensively in products like cellphones and digital cameras and can usually be reprogrammed several thousand times.

Matrix's immediate target for use of its chips is for mask ROM - chips that are loaded in the factory with data or programs that remain unchanged.

Matrix is also trying to exploit a manufacturing advantage over other memory chip makers: its ability to use older, less expensive chip making equipment. It can do so because the vertical approach means the circuits do not have to be etched as tightly to achieve the same capacity.

By using older technology, the company enjoys higher production yields, further reducing the cost of its products.

To build multiple layers - or floors - to pack its data more tightly, Matrix uses a layer of a material referred to as polysilicon to isolate each layer. This technology was first developed for flat-panel displays, where thin film transistors are placed on a thin layer of polysilicon which is then placed on a layer of glass.