IBM Hopes Nanotube Transistors Are Coming Aroud 2020

Computer chips are getting ever smaller, but the miniaturization of silicon transistors has become increasingly tricky. IBM researchers say that it will be able have transistors built using carbon nanotubes ready to take over from silicon transistors by 2020. Intel’s latest chips have transistors with features as small as 14 nanometers. By 2020, transistors must have features as small as five nanometers in order to keep up with Moore’s Law, and keep up with the continuous miniaturization of computer chips. But it is unclear how the industry can keep scaling down silicon transistors much further or what might replace them.

IBM is aiming to have transistors built using carbon nanotubes ready to take over from silicon transistors soon after 2020.

Wilfried Haensch leads IBM's nanotube project at the company’s T.J. Watson research center in Yorktown Heights, New York. He says that nanotubes are the only technology that looks capable of keeping the advance of computer power from slowing down, by offering a practical way to make both smaller and faster transistors.

In 1998, researchers at IBM made one of the first working carbon nanotube transistors. But this is the first time IBM hopes nanotubes can step into commecrial applications.

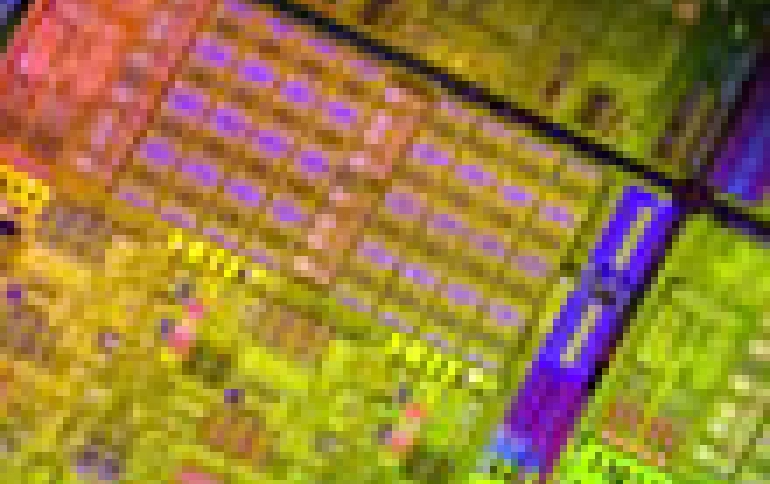

IBM has already developed chips with 10,000 nanotube transistors and now it is working on a transistor design that could be built on the silicon wafers used in the industry today with minimal changes to existing design and manufacturing methods.

IBM’s design uses six nanotubes lined up in parallel to make a single transistor. Each nanotube is 1.4 nanometers wide, about 30 nanometers long, and spaced roughly eight nanometers apart from its neighbors. Both ends of the six tubes are embedded into electrodes that supply current, leaving around 10 nanometers of their lengths exposed in the middle. A third electrode runs perpendicularly underneath this portion of the tubes and switches the transistor on and off to represent digital 1s and 0s.

According to simulations that evaluated the performance of a chip with billions of transistors, that the design chosen should allow a microprocessor to be five times as fast as a silicon one using the same amount of power.

However, IBM researchers have not found a way to position the nanotubes closely enough together, because existing chip technology can’t work at that scale. The favored solution is to chemically label the substrate and nanotubes with compounds that would cause them to self-assemble into position. Those compounds could then be stripped away, leaving the nanotubes arranged correctly and ready to have electrodes and other circuitry added to finish a chip.

Last year researchers at Stanford created the first simple computer built using only nanotube transistors . But those components were bulky and slow compared to silicon transistors.

For now, IBM’s nanotube effort remains within its research labs, not its semiconductor business unit. This means that success is not guaranteed.

Other alternatives that could take over from silicon transistors could be devices that manipulate the spin of individual electrons (Silicon-Based Spintronics).