IBM Cools Chips By Streaming Water Inside

IBM researchers believe that sloshing water through hair-thin pipes inside chips will solve heat problems facing next-generation computers.

As chips get smaller and smaller, cramming more

processing power into ever-tinier spaces, the heat

thrown off by the miniature circuits becomes harder to

manage. Cooling measures used now to avoid chip

meltdowns, including "heat sinks" made from

heat-absorbing materials, might not work on tinier

scales.

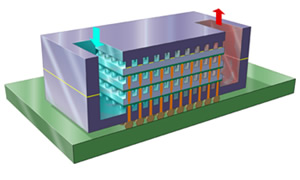

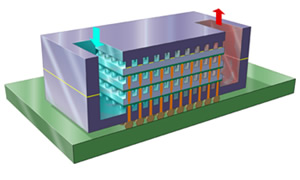

In a future microprocessor design IBM is exploring called 3-D Chips, chips are stacked vertically to save space and enhance performance, rather than arrayed next to each other. In this design, the heat-to-volume ratio exceeds that of a nuclear reactor.

To address that, IBM researchers say they could pipe

water in between chips that are sandwiched together. The

system uses pipes that are just 50 microns wide - 50 millionths of a meter. The tiny tubes are sealed to prevent leaks and electrical shorts.

To address that, IBM researchers say they could pipe

water in between chips that are sandwiched together. The

system uses pipes that are just 50 microns wide - 50 millionths of a meter. The tiny tubes are sealed to prevent leaks and electrical shorts.

Even these micro amounts of water can handle prodigious cooling chores, because water is much more efficient than air at absorbing heat. That is why some high-end computers long have used water cooling. The new trick here is that IBM expects to do it at the miniature scale, inside chips.

"As we package chips on top of each other to significantly speed a processor?s capability to process data, we have found that conventional coolers attached to the back of a chip don?t scale. In order to exploit the potential of high-performance 3-D chip stacking, we need interlayer cooling," explains Thomas Brunschwiler, project leader at IBM?s Zurich Research Laboratory. "Until now, nobody has demonstrated viable solutions to this problem."

Using the superior thermophysical qualities of water, scientists were able to demonstrate a cooling performance of up to 180 W/cm2 per layer for a stack with a typical footprint of 4 cm2.

"This truly constitutes a breakthrough. With classic backside cooling, the stacking of two or more high-power density logic layers would be impossible," said Bruno Michel, manager of the chip cooling research efforts at the IBM Zurich Lab.

However, IBM's tiny pipes aren't out of the lab yet. They're at least five years from becoming available. In further research, IBM is working to optimize cooling systems for even smaller chip dimensions and more interconnects. They are also investigating additional sophisticated structures for hotspot cooling.

In a future microprocessor design IBM is exploring called 3-D Chips, chips are stacked vertically to save space and enhance performance, rather than arrayed next to each other. In this design, the heat-to-volume ratio exceeds that of a nuclear reactor.

To address that, IBM researchers say they could pipe

water in between chips that are sandwiched together. The

system uses pipes that are just 50 microns wide - 50 millionths of a meter. The tiny tubes are sealed to prevent leaks and electrical shorts.

To address that, IBM researchers say they could pipe

water in between chips that are sandwiched together. The

system uses pipes that are just 50 microns wide - 50 millionths of a meter. The tiny tubes are sealed to prevent leaks and electrical shorts.

Even these micro amounts of water can handle prodigious cooling chores, because water is much more efficient than air at absorbing heat. That is why some high-end computers long have used water cooling. The new trick here is that IBM expects to do it at the miniature scale, inside chips.

"As we package chips on top of each other to significantly speed a processor?s capability to process data, we have found that conventional coolers attached to the back of a chip don?t scale. In order to exploit the potential of high-performance 3-D chip stacking, we need interlayer cooling," explains Thomas Brunschwiler, project leader at IBM?s Zurich Research Laboratory. "Until now, nobody has demonstrated viable solutions to this problem."

Using the superior thermophysical qualities of water, scientists were able to demonstrate a cooling performance of up to 180 W/cm2 per layer for a stack with a typical footprint of 4 cm2.

"This truly constitutes a breakthrough. With classic backside cooling, the stacking of two or more high-power density logic layers would be impossible," said Bruno Michel, manager of the chip cooling research efforts at the IBM Zurich Lab.

However, IBM's tiny pipes aren't out of the lab yet. They're at least five years from becoming available. In further research, IBM is working to optimize cooling systems for even smaller chip dimensions and more interconnects. They are also investigating additional sophisticated structures for hotspot cooling.