Near-field Recording: Beyond Blu-Ray

Philips researchers have made significant progress in developing a new storage technology called near-field optical recording. The technology boosts capacity to 150 gigabytes stored on two layers of an optical media, not very different from today's DVDs. The Near-field optical recording terminology refers to the extremely short distance between the read/write head and the disc surface. The roughly 25-nm gap is directly comparable to the distance between the head and the disk surface in hard-disk assemblies.

As in the case of Blu-Ray, the fundumental for achieving large storage capacities is to increase the data density recorded on the medium. But the data density of an optical recording medium depends on the focused laser beam spot size, which is limited by diffraction. The beam spot size can be reduced by using a shorter wavelength laser or a larger Numerical Aperture (NA) objective lens. In the case of CD media, we are talking about a 780nm laser and 0.45 NA (0.7GB), for DVD we have 650nm and 0.6 NA (4.7GB) and for the Blu-Ray there will be a "blue" 405nm laser, 0.85 NA (25GB).

Philips' approach for high density recording under the near field recording concept uses a 405 nm laser beam, focused by a pair of special lenses that offer a NA of 1.5-20! Through this, the capacity of a DVD medium can reach 150GB or more, on two layers.

The challenge for Philips engineers was the development of a high NA lens system combined with a low-hovering recording head.

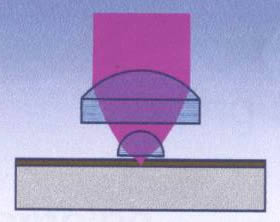

The answer is to use a blue laser to write and read data through a "solid immersion lens" (SIL). This type of optics is already used in microscopes and in lithography equipment for semiconductor production. The SIL uses the different refractive index of glass and air to achieve a high numerical aperture. The SIL optical head is composed of a hemisphere which is made from high refractive index glass and high NA focusing objective lens.

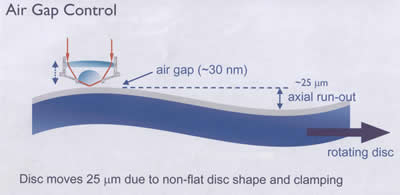

The SIL reduces the spot size of the focused beam at the bottom of that lens.After having achieved the high NA, Philips had to make sure that the laser head would be able to accurately hover above the medium surface at distances that were roughly 25nm. A central ingredient of Philips' new technology is a servo that controls the position of the read/write head. For its tests on a Near field recording set-up, Philips mounted the lens in a conventional DVD actuator, currently used for focusing and tracking. Trials by Philips and Sony have shown that actuators are more robust than sliders, even at an extremely short distance. The actuator was combined with a Gap Error Signal (GES) and an electronic servo controller. The GES is made by intergrating all the light, which is reflected from the disc and has a perpendicular polarization with respect to the incident light. Without precautions, this would mean that the GES depends on the power emmited by the laser. This is remedied by normalizing the GES with a low-pass filtered forward sense signal, which directly monitors the laser output power. For radial tracking, the conventional single spot push-pull method was used. The experimental results indicate that by this method, a

The SIL reduces the spot size of the focused beam at the bottom of that lens.After having achieved the high NA, Philips had to make sure that the laser head would be able to accurately hover above the medium surface at distances that were roughly 25nm. A central ingredient of Philips' new technology is a servo that controls the position of the read/write head. For its tests on a Near field recording set-up, Philips mounted the lens in a conventional DVD actuator, currently used for focusing and tracking. Trials by Philips and Sony have shown that actuators are more robust than sliders, even at an extremely short distance. The actuator was combined with a Gap Error Signal (GES) and an electronic servo controller. The GES is made by intergrating all the light, which is reflected from the disc and has a perpendicular polarization with respect to the incident light. Without precautions, this would mean that the GES depends on the power emmited by the laser. This is remedied by normalizing the GES with a low-pass filtered forward sense signal, which directly monitors the laser output power. For radial tracking, the conventional single spot push-pull method was used. The experimental results indicate that by this method, a

stable air gap on polycarbonate discs is achieved, even at 3600 RPM.

Philips researchers have made significant progress over the last 12 months, and the company's spoksemen claim that the technology is quite robust.

The servo technolgy will be at the center of the company's presentation next week at the International Symposium on Optical Memory and Optical Data Storage in Hawaii.

The next step for Philips will be the implementation of Near Field Recording technology in upcoming CD, DVD and Blu-Ray media. This would require the manufacturing of a polymer cover-layered disc, in two layers.

Commerciallization, however, of this research project is several years away.