Tiny Hard Disk Used To Store Huge Amounts Of Data, Atom by Atom

A team of scientists at the Kavli Institute of Nanoscience at Delft University achieved a storage density that could allow all books ever created by humans to be written on a single post stamp. The researchers built a memory of 1 kilobyte (8,000 bits), where each bit is represented by the position of one single chlorine atom. They reached a storage density of 500 Terabits per square inch (Tbpsi), 500 times better than the best commercial hard disk currently available.

In 1959, physicist Richard Feynman challenged his colleagues to engineer the world at the smallest possible scale. In his famous lecture There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom, he speculated that if we had a platform allowing us to arrange individual atoms in an exact orderly pattern, it would be possible to store one piece of information per atom. To honor the visionary Feynman, lead-scientist Sander Otte and his team now coded a section of Feynman’s lecture on an area 100 nanometers wide.

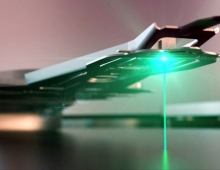

The team used a scanning tunneling microscope (STM), in which a sharp needle probes the atoms of a surface, one by one. With these probes scientists cannot only see the atoms but they can also use them to push the atoms around. "You could compare it to a sliding puzzle", Otte explains. "Every bit consists of two positions on a surface of copper atoms, and one chlorine atom that we can slide back and forth between these two positions. If the chlorine atom is in the top position, there is a hole beneath it -- we call this a 1. If the hole is in the top position and the chlorine atom is therefore on the bottom, then the bit is a 0." Because the chlorine atoms are surrounded by other chlorine atoms, except near the holes, they keep each other in place. That is why this method with holes is much more stable than methods with loose atoms and more suitable for data storage.

The researchers from Delft organized their memory in blocks of 8 bytes (64 bits). Each block has a marker, made of the same type of 'holes' as the raster of chlorine atoms. Inspired by the pixelated square barcodes (QR codes) often used to scan tickets for airplanes and concerts, these markers work like miniature QR codes that carry information about the precise location of the block on the copper layer. The code will also indicate if a block is damaged, for instance due to some local contaminant or an error in the surface. This allows the memory to be scaled up easily to very big sizes, even if the copper surface is not entirely perfect.

The new approach offers excellent prospects in terms of stability and scalability. Still, this type of memory should not be expected in datacenters soon. Otte: "In its current form the memory can operate only in very clean vacuum conditions and at liquid nitrogen temperature (77 K), so the actual storage of data on an atomic scale is still some way off. But through this achievement we have certainly come a big step closer".